PRESS RELEASE

Women of the Kivalliq and Kitikmeot

Sep 11 – Nov 20, 2014

This exhibition features the work of 24 women from communities west of Hudson's Bay: Arviat, Baker Lake, Coppermine, Rankin Inlet and Taloyoak. The works span the media that were available in the area: sculptures, original drawings, prints, wall hangings and one ceramic piece.

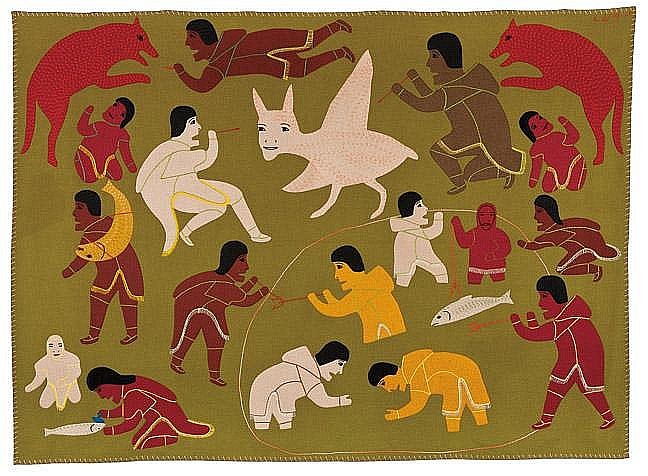

The works cluster around two themes: the intimacy of family relationships, and the power of shamanism. These two themes are improbably but beautifully combined in the keynote work for the exhibition, Victoria Mamguqsualuq’s masterful wallhanging that features lovingly detailed scenes from a fishing weir on the bottom half, and on the top half a hunting scene that is dominated by a bird-human creature.

Family relationships dominate the carvings in two senses. First, most of the carvings depict family groupings, some of which are surprising. Ada Eyetoaq’s small gem appears to be a mother and two children, but on closer inspection turns out to be a mother and child with a bird. Lucy Tasseor Tutsweetok’s minimalist groupings of faces suggest large extended families. These bring to mind Marion Tu’uluq’s wall hangings with many apparently identical faces, but when questioned Marion could put a name to each of the individuals pictured in the wall hanging. Second, the 24 artists include two sets of mother-daughter pairs. Lucy Tasseor Tutsweetok is joined by her daughter, Nancy Tasseor Kablutsiak, and her granddaughter Mary Tutsweetok. Elizabeth Nutaruluk Aulatjut is joined by her daughter, Mary Ayaq Anowtalik (married to artist Luke Anowtalik), who features Elizabeth’s signature braids on one of her sculptures.

Most of the carvings exemplify the minimalist style associated with Arviat and, to a lesser extent, Baker Lake. This is often attributed to the fact that the local stone in the western communities is much denser and harder to work than the serpentine of southern Baffin Island. There are, however, notable counterexamples. Maudie Okittuq’s Transformation features sensuous curves, carved out of the stone, in contrast to Lucy Tasseor Tutsweetok’s minimalist adaptation to the form of the stone.

The graphics and textiles represent a vivid and emphatic departure from the restrained carvings. The theme of shamanism is developed with vigor and without constraints. Irene Avaalaaqiaq Tiktaalaaq’s wall hangings feature a universe of cheerful inter-specific transformations. Works by Janet Kigusiuq, Jessie Oonark and Marion Tu’uluq positively explode with color. Finally, Ruth Tulurialik’s Shaman Family resolves the apparent contradiction between the two themes. Shamanism is not distinct from the families featured in the carvings; the shaman has a family, complete with children and extended relatives. It is part of the “normal” world.